Making Emotional AI familiar: a narrative approach for researching citizen perspectives online

Alexander Laffer

As part of the Emotional AI in Cities project, I was tasked with designing and running workshops to collect citizen perspectives on living well with Emotional AI. This raised a number of issues, largely due to participants unfamiliarity with the emergent technology and the broad range and variation in emotional AI use. (You can get a fuller description of Emotional AI here.)

To overcome these issues, an innovative narrative approach was designed. Workshop participants were taken through a piece of interactive fiction which introduced them to emotional AI in domesticated (Auger, 2013) forms that rendered it familiar, even mundane. This approach encouraged participants to consider the impact emotional AI might have on their lives and practices, rather than focussing on the underlying technology.

The full workshop narrative can be found here.

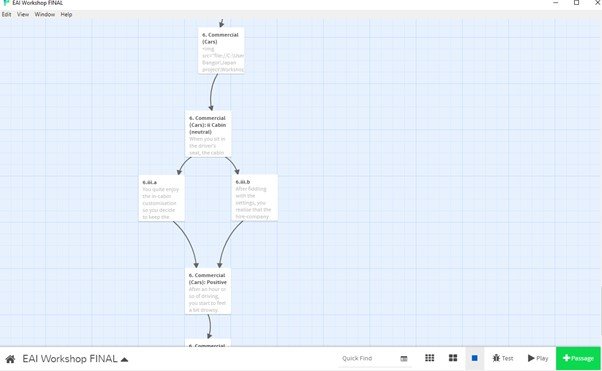

The creation of the narrative drew on Design Fiction (Bleecker, 2009; Markussen & Knutz, 2013), incorporated elements of ContraVision (Mancini et al., 2010) and was created using Twine, an interactive fiction tool. I’ll briefly explain each:

Design Fiction

An approach used to explore the impact and influence of technology on lives, social institutions and norms through diegetic prototypes (Bosch, 2012; Sterling, 2013) – designed objects or technologies that exist within a fictional world – and narratives.

ContraVision

The repeated presentation of a narrative showing the use of technology with competing positive and negative outcomes. This was adapted for the current project with different outcomes created for a pair of sequential events. This allowed for a continuous narrative and sustained immersion in the story.

Twine

An interactive fiction writing tool that enables the simple construction and delivery of multimodal narratives. Further information on Twine can be found here.

The eventual story took the form of a ‘day-in-the-life’ narrative, following a protagonist – addressed in the second person (“you) – as they encountered different uses cases (and forms) of emotional AI:

A home-hub smart assistant (Voice analysis)

A bus station surveillance sensor (Biometric sensor)

Social Media fake news and disinformation (Emotional profiling and triggering)

Spotify music recommender (Voice and ambient analysis)

A sales call evaluation and prompt tool (Voice and facial expression analysis)

An emotoy (Voice and movement analysis)

A hire-car automated system (Biometric, voice and movement analysis)

Each use case followed a sequence of a) a neutral introduction of the technology; b) a binary choice emerging from the use of the technology; c) the ContraVision element with a positive and negative event/outcome. In this way, we were able to surface key themes, prompt consideration of particular aspects of use and encourage a range of potential responses while leaving space for the participants to bring their own ideas and pre-occupations to the discussion.

This innovative new narrative approach was highly effective in practice. Benefits included:

Increased engagement, avoiding participant fatigue and leading to rich data

Mitigation of variation in participants’ digital literacy

Encouragement of a greater diversity of responses

Quick familiarisation with abstract and unfamiliar topics

Overcoming individual and group differences through shared encounters in a co-constructed story world

Supporting a focus on people and social practices even while exploring the impacts of new technologies

Promotion of immersion and empathy with potential users to progress discussion beyond technical considerations

The approach would be particularly useful for research that requires consideration of any of the following: emergent or future technology; citizen attitudes; participants’ lived experiences.

A fuller account of the development and implementation of this approach is being published as a case study by SAGE.

Twine Narrative: Emotional AI in Cities

References

Auger, J. (2013). Speculative design: Crafting the speculation. Digital Creativity, 24(1), 11–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2013.767276

Bleecker, J. (2009). Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction. Near Future Laboratory. http://blog.nearfuturelaboratory.com/2009/03/17/ design-fiction-a-short-essay-on-design-science-fact-and-fiction/

Bosch, T. (2012, March 2). Sci-Fi Writer Bruce Sterling Explains the Intriguing New Concept of Design Fiction. Slate. https://slate.com/technology/2012/03/bruce-sterling-on-design-fictions.html

Mancini, C., Rogers, Y., B, A. K., Coe, T., & Jedrzejczyk, L. (2010). ContraVision: Exploring Users ’ Reactions to Futuristic Technology. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753350

Markussen, T., & Knutz, E. (2013). The poetics of design fiction. DPPI ’13: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, 231–240. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2513506.2513531

Sterling, B. (2013). Patently untrue: Fleshy defibrillators and synchronised baseball are changing the future. Wired UK. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/patently-untrue

Dr Alexander Laffer is a lecturer in linguistics and digital media whose work combines research and creative practice. He has received DEK and Santander Universities funding for projects that apply linguistic knowledge to support local enterprise. As a consultant, he has delivered projects for organisations such as the Southbank Centre, the UK’s largest arts centre. He is a research officer on the project Emotional AI in Cities.

Advert for a fictional tech company used in Emotional AI in Cities workshop

Packaging for Emotoy diegetic prototype

Twine Author View of Emotional AI in Cities narrative